This photograph, a cabinet card from the 1870s, is in my private collection.

This girl has cool attitude long before the term is coined. In her own time period, depending on her behavior, a little girl whose actions matched this posture might be known as a tomboy — a girl too much like a boy. * see disclaimer at end of this post.

We’ve had the pleasure of watching three eminently cool political leaders – Barack Obama, Joe Biden, Michelle Obama – serve for the past eight years. What makes each of these three people – who wear their hearts on their sleeves – cool?

Each person has been photographed with tears in their eyes; a display of emotion once understood as the end of an American political life. Barack Obama openly cries when talking about the victims of the Sandy Hook murders; Biden tears up when surprised with the Medal of Freedom; Michelle Obama tears up as she delivers her final speech as First Lady to a group of guidance counselors (all women but for one stellar man). These emotional displays are a component of the cool persona of each person: Barack Obama Biden, Michelle: each embodies a cool attitude, a kind of ironic distance with the social context but a close engagement with the members of the audience.

How is it that the little girl from 1870s Detroit appears “cool” to us? She doesn’t fit the profile for someone being cool: she’s white, a girl, and from the 1800s. Cool as a term came into use… who knows when? There’s some faint hints: Shakespeare uses the term to signify a lack of impetuosity, so characters are urged to have “cool reason” or “cool patience.” In other words, take a breath, use your reason and don’t be so reactive. Even in Beowulf centuries before, emotions ran hot, then cooled. (This argument is taken from Mike Vuolo’s “The Birth of Cool” essay for Slate in 2013, by the way.)

What’s useful here is Coolness = Distance — an emotional distance from the immediate action. Then, in the U.S. coolness took its contemporary form, and like nearly every freaking good thing produced by American culture, it was all about the confluence of African American culture and the uniquely monetized popular culture of the U.S. Hard to know for sure, but “cool” in its contemporary meaning arose, it seems, from enslaved Africans, who said something was “cool” as a sign of approval. People weren’t cool, but something could be cool. In the 1920s the term cool starts showing up in jazz songs, jazz poetry, and usually means that a person, often a man, is cool. Those cool men are also men who break hearts, scam their way to riches — men who figure out how to game a system stacked against them.

Coolness = Distance. That’s one part of the equation of coolness. The other is related to the original connotation of rationality. Philosopher Throsten Botz-Bornstein in his essay from 2010 “What Does It Mean to Be Cool?” from Philosophy Now: a magazine of ideas, argues that “cool resists linear structures” (italics in original). Please let that sink in a bit, because damn, it’s sharp. “Cool resists linear structures”: that means that, as Botz-Bornstein continues, “Coolness is a nonconformist balance that manages to square circles and to personify paradoxes.”

Coolness, therefore, is getting what you want by balancing needs, wants, emotions, goals — as Janelle Monáe sings, “whether you’re high or low, you gotta tip on the tightrope”. And a cool person doesn’t get freaked out when others want something different — in fact, coolness retains that Shakespearean imperative to be rational. A cool person doesn’t get upset because new demands are placed on them, or if someone wants something different than the cool person: a cool person works just a wee bit within the rules, toggling between the ropes of constraint and action.

In this snapshot from the 1940s or very early 1950s from my private collection, we can see coolness even as it teeters on the brink of washed-up-ness. He’s a cool dude. Why? Coolness comes from distance and resistance. Here, the hand in the pants pocket and the lit cigarette in his other hand suggest the detachment required to be cool. He is playing by the rules — kind of. His clothes are suitable in the most literal sense, being a suit, shirt, tie, pocket square. But resistance is evident as well — the tie is a light-toned gingham -plaid and most unexpectedly, his pocket square is an exaggerated version of the pattern of the tie. And there’s that narrow downward-turning mustache — just a shade too dashing, as are the flaring, high cheekbones. This guy is just on the edge of seedy but he’s not a loser, by any means. He has, by meeting life (and the viewer/camera) head on, surmounted the circumstances. He comes off as self-contained, available and yet detached.

His direct look echoes that of our cool girl from the 1870s. Coolness, Botz-Bornstein points out, is not about “not caring”; it’s about connection with distance, about living immersed in a culture you are alienated from. Considering the origins of coolness in Black American culture, that makes sense. No matter how well African Americans played by the rules, followed every dictate, they were always held at a distance, never fully rewarded.

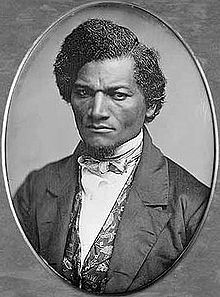

This is why, jumping backwards in time, Frederick Douglass is one of the cool men of American history. That direct gaze is the connection but as his extraordinary autobiography demonstrates, Douglass was painfully, acutely aware that white America was never, ever going to accept him or Black folk. Douglass proceeded to live an American life on his own terms but with an intangible emotional distance from the world about him. Linear straightforward approaches to change and power led to nowhere so Douglass got somewhere by balancing demands and paths. He walked the tightrope strung by whites and by not caring what they thought, forced white America to pay close attention to him as he navigated a world he subtly set the terms for.

Coolness is embodied. That distance and alienation from whatever constitutes the cool individual’s world, paired with their ability to resist the straightforward paths to acceptance, is demonstrated through what seems like natural behavior. This snapshot from my personal collection gives a sense of this. The younger girl to the right is cooler than her older sister to the left. As the caption on the back attests, these two were photographed by their mother next to the cabin the family rented “out west” (the girls are wearing their “dude ranch boots”). The younger girl embodies coolness: her straight shoulders, the grin, the hand on the hip – she’s a distinct individual. Her older sister’s posture suggests embarrassment or discomfort, with her shoulders rolled in, stomach curved out, hand held stiffly at her side: she’s determinedly posing for the photographer. The older sibling wants badly to do what the photographer has told her to; the younger girl blithely follows her bliss, unconcerned about appealing to the directives.

This tintype from the 1860s (I’m guessing on that: there are clues: the plaid fabric, the lack of a collar and the trimming to suggest one, the ‘bow tie’, and the large dangling earrings). She’s bordering on the uncool, isn’t she? She just too much: that bow tie, that plaid! a choker above the bow tie, those long triple-rows of dangling “gems” on her earrings. The hair. First off, her hair might be in an exceedingly awkward growing-out stage; it isn’t a myth that girl’s hair was cut if they were suffering a serious illness. The puffy discoloration under her eyes supports the serious-illness theory. But still! Her hair, cavorting every which way. And leaving her somewhat large ear displayed for all to see (an unusual choice of hair arrangement; most young women with prominent ears would have arranged their hair over the top half of the ears). She’s a bit off-kilter and yet confident; not so sure of the world she lives in but resourceful in dealing with it. I’ve always imagined (it’s from my private collection) that she was indeed seriously ill and now, gamely and bravely showing her colors as she regains her health. Perhaps she’s been to hell and back and is no longer afraid. Coolness shows up in the most surprising of places, times, and in the most unusual of people.

*disclaimer: in middle school to about your mid-twenties, there are two kinds of “cool.” One is narrowly focused on social popularity, usually measured by expensive clothing and accessories, membership in the “popular” group that wields the highest degree of exclusionary power paired with a vicious struggle within ranks (think Mean Girls), and a social hierarchy in which proper romantic/sexual pairings are based on equivalencies of peer status (hence the stereotypical pairing of football star+head cheerleader). The second kind of cool is the authentic embodiment of a distancing from the socio-economic struggles of the first. A “cool” kid is one who enjoys social popularity based on intangible qualities of character (such as a disinclination to bully), the ability to navigate multiple levels of economic status (so that one’s status is not dependent on one’s parental wealth), and possession of an unflappability when faced with loss of status (in other words, a person who doesn’t particularly care about one’s status as cool, will render that person cool). In this way, “true” cool tied to embodiment of distance, behavioral engagement with kindness, and a detachment from the markers of “popularity” (such as, in middle school, possession of Ugg or Hunter boots; wearing of NFL gear, participation in specific sports or activities) render a person truly cool. And after one’s mid-twenties, if you are a person ready to be yourself, independent of other’s constant approval — you gain cool from dressing in your own way, indulging in hobbies and interests that might have doomed you in middle school. Cool is loving Renfair, Comic Cons, monster trucks, collecting fossils, photographing birds, cataloging types of doors, volunteering.

I thought the last one looked like mental illness, like those click-bait sets of pics from a turn-of-the-century mental institution. Although I guess she would be too well-dressed (or at least dressed with too many clothing items!)

It’s hard to know what to make of her appearance. Taking her for her time period, the layering of those accessories is a bit off, but someone – maybe her, maybe someone caring for her — paid careful attention to that white blouse and that ‘bowtie’. Illness seemed a good explanation (mental illness could fall under that category).

Pingback: Striking! | Style of Resistance